第 5 章 字体 Fonts

第 5 章 字体 Fonts

The beginning of the “Font Properties” section of the CSS1 specification, written in 1996, begins with this sentence: “Setting font properties will be among the most common uses of style sheets.” The intervening years have done nothing to disprove this assertion.

CSS1 规范中“字体属性”一节的开头是这样写的:“设置字体属性将是样式表最常见的用法之一。从那以后的几年中,没有发生任何事情来反驳这种说法。

CSS2 added the ability to specify custom fonts for download with @font-face, but it wasn’t until about 2009 that this capability really began to be widely and consistently supported. Now, websites can call on any font they have the right to use, aided by online services such as Typekit. Generally speaking, if you can get access to a font, you can use it in your design.

CSS2 增加了使用“@font-face”为下载指定自定义字体的功能,但直到 2009 年左右,这项功能才真正开始得到广泛和一致的支持。现在,在 Typekit 等在线服务的帮助下,网站可以调用任何他们有权使用的字体。一般来说,如果你可以使用一种字体,你可以在你的设计中使用它。

It’s important to remember, however, that this does not grant absolute control over fonts. If the font you’re using fails to download, or is in a file format the user’s browser doesn’t understand, then the text will be displayed with a fallback font. That’s a good thing, since it means the user still gets your content, but it’s worth bearing in mind that you cannot absolutely depend on the presence of a given font and should never design as if you can.

但是,要记住,这并不授予字体的绝对控制权。如果您使用的字体下载失败,或者是用户的浏览器不理解的文件格式,那么文本将使用回退字体显示。这是一件好事,因为这意味着用户仍然可以获得您的内容,但值得记住的是,您不能完全依赖于给定字体的存在,并且永远不应该设计成您可以这样。

5.1 Font Families

What we think of as a “font” is usually composed of many variations to describe bold text, italic text, and so on. For example, you’re probably familiar with (or at least have heard of) the font Times. However, Times is actually a combination of many variants, including TimesRegular, TimesBold, TimesItalic, TimesBoldItalic, and so on. Each of these variants of Times is an actual font face, and Times, as we usually think of it, is a combination of all these variant faces. In other words, Times is actually a font family, not just a single font, even though most of us think about fonts as being single entities.

我们所认为的“字体”通常由许多变体组成,用以描述粗体文本、斜体文本等等。例如,您可能熟悉(或至少听说过)字体时间。然而,Times 实际上是许多变体的组合,包括 TimesRegular、TimesBold、TimesItalic、TimesBoldItalic 等等。Times 的每个变体都是一个实际的“字体面”,而 Times,我们通常认为,是所有这些变体面的组合。换句话说,Times 实际上是一个“字体族”,而不是单一的字体,尽管我们大多数人认为字体是单一实体。

In order to cover all the bases, CSS defines five generic font families:

为了涵盖所有的基础,CSS 定义了五种通用字体:

Serif fonts

These fonts are proportional and have serifs. A font is proportional if all characters in the font have different widths due to their various sizes. For example, a lowercase i and a lowercase m are different widths. (This book’s paragraph font is proportional, for example.) Serifs are the decorations on the ends of strokes within each character, such as little lines at the top and bottom of a lowercase l, or at the bottom of each leg of an uppercase A. Examples of serif fonts are Times, Georgia, and New Century Schoolbook.

这些字体是成比例的,并且有序列化。如果字体中的所有字符由于大小不同而具有不同的宽度,则字体是成比例的。例如,小写的“i”和小写的“m”是不同的宽度。(比如,这本书的段落字体是成比例的。)衬线是每个字符笔画末端的装饰,比如小写“l”的顶部和底部的小线条,或者大写“a”的每条腿的底部。衬线字体的例子有 Times、Georgia 和 New Century 教科书。

Sans-serif fonts

These fonts are proportional and do not have serifs. Examples of sans-serif fonts are Helvetica, Geneva, Verdana, Arial, and Univers.

这些字体是成比例的,没有衬线。“无衬线字体”的例子有 Helvetica、Geneva、Verdana、Arial 和 Univers。

Monospace fonts

Monospace fonts are not proportional. These generally are used for displaying programmatic code or tabular data. In these fonts, each character uses up the same amount of horizontal space as all the others; thus, a lowercase i takes up the same horizontal space as a lowercase m, even though their actual letterforms may have different widths. These fonts may or may not have serifs. If a font has uniform character widths, it is classified as monospace, regardless of the presence of serifs. Examples of monospace fonts are Courier, Courier New, Consolas, and Andale Mono.

等宽字体不成比例。这些通常用于显示编程代码或表格数据。在这些字体中,每个字符占用的水平空间与其他字体相同;因此,小写的“i”与小写的“m”占据相同的水平空间,尽管它们的实际字母形式可能具有不同的宽度。这些字体可能有,也可能没有。如果字体具有统一的字符宽度,则将其归类为 monospace,而不管是否存在衬线。monospace 字体的例子有 Courier、Courier New、Consolas 和 Andale Mono。

Cursive fonts

These fonts attempt to emulate human handwriting or lettering. Usually, they are composed largely of flowing curves and have stroke decorations that exceed those found in serif fonts. For example, an uppercase A might have a small curl at the bottom of its left leg or be composed entirely of swashes and curls. Examples of cursive fonts are Zapf Chancery, Author, and Comic Sans.

这些字体试图模仿人类的笔迹或字母。通常,它们主要由流动的曲线组成,并且有超过衬线字体的笔画装饰。例如,大写字母“A”可能在左腿底部有一小段卷发,或者完全由斜线和卷发组成。草体字体的例子有 Zapf Chancery、Author 和 Comic Sans。

Fantasy fonts

Such fonts are not really defined by any single characteristic other than our inability to easily classify them in one of the other families (these are sometimes called “decorative” or “display” fonts). A few such fonts are Western, Woodblock, and Klingon.

这些字体并不是由任何单一的特征来定义的,除了我们无法简单地将它们归类到其他类别中(这些字体有时被称为“装饰性”或“显示性”字体)。有一些这样的字体是西方的、雕版的和克林贡的。

In theory, every font family will fall into one of these generic families. In practice, this may not be the case, but the exceptions (if any) are likely to be few and far between, and browsers are likely to drop any fonts they cannot classify as serif, sans-serif, monospace, or cursive into the “fantasy” bucket.

从理论上讲,每一种字体都属于这一类。在实践中,情况可能并非如此,但例外情况(如果有的话)可能很少,而且相差甚远,浏览器可能会将无法归类为 serif、sans-serif、monospace 或花体字体的字体删除到“幻想”桶中。

5.1.1 Using Generic Font Families

You can call on any available font family by using the property font-family.

您可以调用任何可用的字体家族使用属性' font-family '。

If you want a document to use a sans-serif font, but you do not particularly care which one, then the appropriate declaration would be:

如果您希望文档使用无衬线字体,但是您并不特别关心使用哪种字体,那么适当的声明应该是:

body {

font-family: sans-serif;

}This will cause the user agent to pick a sans-serif font family (such as Helvetica) and apply it to the body element. Thanks to inheritance, the same font family choice will be applied to all the elements that descend from the body—unless a more specific selector overrides it.

这将导致用户代理选择一个 sans-serif 字体族(如 Helvetica)并将其应用于“body”元素。由于继承,同样的字体族选择将被应用到所有的元素,从“身体”-除非一个更具体的选择覆盖它。

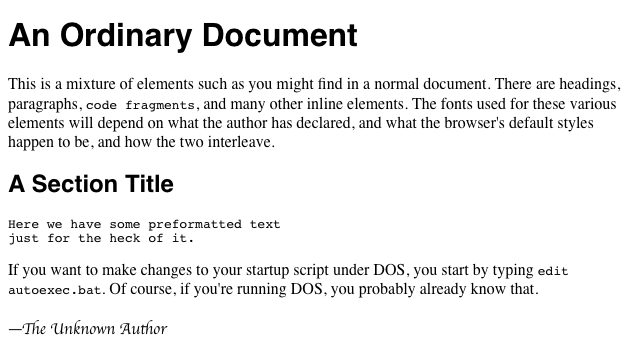

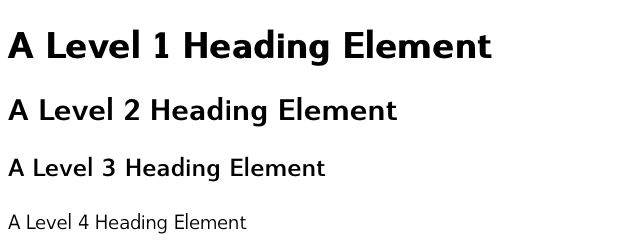

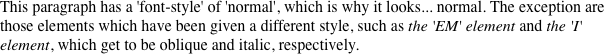

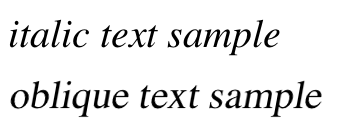

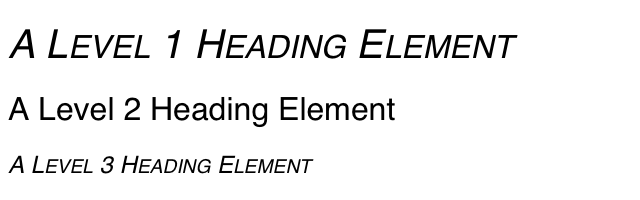

Using nothing more than these generic families, an author can create a fairly sophisticated stylesheet. The following rule set is illustrated in Figure 5-1:

只需使用这些泛型系列,作者就可以创建相当复杂的样式表。下面的规则集如图 5-1 所示:

body {font-family: serif;}

h1, h2, h3, h4 {font-family: sans-serif;}

code, pre, tt, kbd {font-family: monospace;}

p.signature {font-family: cursive;}

.Thus, most of the document will use a serif font such as Times, including all paragraphs except those that have a class of signature, which will instead be rendered in a cursive font such as Author. Heading levels 1 through 4 will use a sans-serif font like Helvetica, while the elements code, pre, tt, and kbd will use a monospace font like Courier.

因此,大多数文档将使用衬线字体,如 Times,包括所有段落,除了那些有“类”的“签名”,它将被呈现为草书字体,如 Author。标题 1 至 4 级将使用无衬线字体,如 Helvetica,而元素' code '、' pre '、' tt '和' kbd '将使用 monospace 字体,如 Courier。

图 5-1: Various font families

// 5-1

5.1.2 Specifying a Font Family

An author may, on the other hand, have more specific preferences for which font to use in the display of a document or element. In a similar vein, a user may want to create a user stylesheet that defines the exact fonts to be used in the display of all documents. In either case, font-family is still the property to use.

另一方面,作者可能对在文档或元素的显示中使用哪种字体有更具体的首选项。类似地,用户可能希望创建一个用户样式表,它定义在显示所有文档时使用的字体。在这两种情况下,“font-family”仍然是要使用的属性。

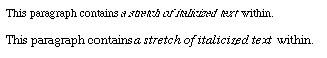

Assume for the moment that all h1s should use Georgia as their font. The simplest rule for this would be the following:

假设现在所有的 h1 都应该使用 Georgia 字体。最简单的规则如下:

h1 {

font-family: Georgia;

}This will cause the user agent displaying the document to use Georgia for all h1s, as shown in Figure 5-2.

这将导致显示文档的用户代理对所有“h1”使用 Georgia,如图 5-2 所示。

图 5-2: An h1 element using Georgia

This rule assumes that the user agent has Georgia available for use. If it doesn’t, the user agent will be unable to use the rule at all. It won’t ignore the rule, but if it can’t find a font called “Georgia,” it can’t do anything but display h1 elements using the user agent’s default font (whatever that is).

此规则假设用户代理具有可用的 Georgia。否则,用户代理将根本无法使用该规则。它不会忽略这个规则,但是如果它找不到名为“Georgia”的字体,它就只能使用用户代理的默认字体(不管它是什么)来显示“h1”元素。

All is not lost, however. By combining specific font names with generic font families, you can create documents that come out, if not exact, at least close to your intentions.

然而,并不是所有的都失去了。通过将特定的字体名称与通用字体系列组合在一起,您可以创建出来的文档,即使不精确,至少也接近您的意图。

To continue the previous example, the following markup tells a user agent to use Georgia if it’s available, and to use another serif font if it’s not:

为了继续前面的示例,下面的标记告诉用户代理,如果 Georgia 可用,则使用它;如果不可用,则使用另一种 serif 字体:

h1 {

font-family: Georgia, serif;

}If a reader doesn’t have Georgia installed but does have Times, the user agent might use Times for h1 elements. Even though Times isn’t an exact match to Georgia, it’s probably close enough.

如果读者没有安装 Georgia,但有时间,用户代理可能会为“h1”元素使用时间。尽管时间与乔治亚州并不完全匹配,但它可能已经足够接近了。

For this reason, I strongly encourage you to always provide a generic family as part of any font-family rule. By doing so, you provide a fallback mechanism that lets user agents pick an alternative when they can’t provide an exact font match. Here are a few more examples:

出于这个原因,我强烈建议您始终将泛型家族作为任何“泛型家族”规则的一部分。通过这样做,您提供了一种回退机制,允许用户代理在无法提供精确的字体匹配时选择一种替代方法。下面是更多的例子:

h1 {

font-family: Arial, sans-serif;

}

h2 {

font-family: Charcoal, sans-serif;

}

p {

font-family: "Times New Roman", serif;

}

address {

font-family: Chicago, sans-serif;

}If you’re familiar with fonts, you might have a number of similar fonts in mind for displaying a given element. Let’s say that you want all paragraphs in a document to be displayed using Times, but you would also accept Times New Roman, Georgia, New Century Schoolbook, and New York (all of which are serif fonts) as alternate choices. First, decide the order of preference for these fonts, and then string them together with commas:

如果您熟悉字体,您可能在脑海中有许多类似的字体用于显示给定的元素。假设您希望文档中的所有段落都使用 Times 来显示,但是您也可以接受 Times New Roman、Georgia、New Century Schoolbook 和 New York(它们都是衬线字体)作为替代选择。首先,确定这些字体的优先顺序,然后用逗号将它们串在一起:

p {

font-family: Times, "Times New Roman", "New Century Schoolbook", Georgia,

"New York", serif;

}Based on this list, a user agent will look for the fonts in the order they’re listed. If none of the listed fonts are available, then it will just pick an available serif font.

基于此列表,用户代理将按照列出的顺序查找字体。如果没有列出的字体可用,那么它将选择可用的衬线字体。

Using quotation marks

You may have noticed the presence of single quotes in the previous example, which we haven’t seen before. Quotation marks are advisable in a font-family declaration only if a font name has one or more spaces in it, such as “New York,” or if the font name includes symbols such as # or $. Thus, a font called Karrank% should probably be quoted:

您可能已经注意到在前面的示例中出现了单引号,这是我们以前没有见过的。在“font-family”声明中,仅当字体名称中有一个或多个空格(如“New York”),或者字体名称中包含#或$之类的符号时,才建议使用引号。因此,一个名为 Karrank%的字体可能应该被引用:

h2 {

font-family: Wedgie, "Karrank%", Klingon, fantasy;

}If you leave off the quotation marks, there is a chance that user agents will ignore that particular font name altogether, although they’ll still process the rest of the rule.

如果省略引号,则用户代理有可能完全忽略该特定字体名称,尽管它们仍将处理规则的其余部分。

Note that the quoting of a font name containing a symbol is not actually required any more. Instead, it’s recommended, which is as close to describing best practices as the CSS specification ever really gets. Similarly, it is recommended that you quote a font name containing spaces, though again, this is generally unnecessary in modern user agents. As it turns out, the only required quotation is for font names that match accepted font-family keywords. Thus, if you call for a font whose actual name is “cursive,” you’ll definitely need to quote it in order to distinguish it from the value keyword cursive:

注意,实际上不再需要引用包含符号的字体名。相反,它是推荐的,这是最接近于描述 CSS 规范的最佳实践。类似地,建议您引用包含空格的字体名称,不过这在现代用户代理中通常是不必要的。事实证明,唯一需要引用的是与被接受的“字体家族”关键字匹配的字体名称。因此,如果你需要的字体的实际名称是“草书”,你肯定需要引用它,以区分它的价值关键字“草书”:

h2 {

font-family: Author, "cursive", cursive;

}Font names that use a single word (which doesn’t conflict with any of the keywords for font-family) need not be quoted, and generic family names (serif, monospace, etc.) should never be quoted when they refer to the actual generic families. If you quote a generic name, then the user agent will assume that you are asking for a specific font with that name (for example, “serif ”), not a generic family.

使用单个单词(不与“Font -family”的任何关键词相冲突)的字体名称不需要引用,而通用家族名称(“serif”、“monospace”等)在引用实际的通用家族时不应该引用。如果您引用了一个通用名称,那么用户代理将假定您请求的是具有该名称的特定字体(例如,“serif”),而不是一个通用家族。

As for which quotation marks to use, both single and double quotes are acceptable. Remember that if you place a font-family rule in a style attribute, which you generally shouldn’t, you’ll need to use whichever quotes you didn’t use for the attribute itself. Therefore, if you use double quotes to enclose the font-family rule, then you’ll have to use single quotes within the rule, as in the following markup:

至于使用哪个引号,单引号和双引号都是可以接受的。请记住,如果您将“font-family”规则放在“style”属性中(通常不应该这样做),那么您需要使用您没有用于属性本身的任何引号。因此,如果您使用双引号将“font-family”规则括起来,则必须在规则中使用单引号,如下面的标记所示:

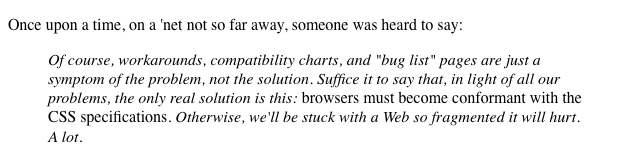

p {

font-family: sans-serif;

} /* sets paragraphs to sans-serif by default */<!-- the next example is correct (uses single-quotes) -->

<p style="font-family: 'New Century Schoolbook', Times, serif;">...</p>

<!-- the next example is NOT correct (uses double-quotes) -->

<p style="font-family: "New Century Schoolbook", Times, serif;">...</p>If you use double quotes in such a circumstance, they interfere with the attribute syntax, as you can see in Figure 5-3.

图 5-3: The perils of incorrect quotation marks

5.2 Using @font-face

A feature that originally debuted in CSS2 but wasn’t implemented until late in the first decade of the 2000s, @font-face lets you use custom fonts in your designs. While there’s no guarantee that every last user will see the font you want, this feature is very widely supported.

“@font-face”这个功能最初出现在 CSS2 上,但直到本世纪头十年的最后几年才得以实现,它可以让你在设计中使用自定义字体。虽然不能保证每个用户都能看到自己想要的字体,但是这个特性得到了广泛的支持。

Suppose you want to use a very specific font in your stylesheets, one that is not widely installed. Through the magic of @font-face, you can define a specific family name to correspond to a font file on your server. The user agent will download that file and use it to render the text in your page, the same as if it were installed on the user’s machine. For example:

假设您想在样式表中使用一种非常特殊的字体,这种字体没有广泛安装。通过“@font-face”的魔力,您可以定义一个特定的姓来对应服务器上的字体文件。用户代理将下载该文件并使用它来呈现页面中的文本,就像安装在用户机器上一样。例如:

@font-face {

font-family: "SwitzeraADF";

src: url("SwitzeraADF-Regular.otf");

}This allows the author to have conforming user agents load the defined .otf file and use that font to render text when called upon via font-family: SwitzeraADF.

这允许作者让符合条件的用户代理加载定义的'。当通过 font-family: aadf 调用时,使用该字体呈现文本。

The examples in this section refer to SwitzeraADF, a font face collection available from the Arkandis Digital Foundry.

The intent of @font-face is to allow lazy loading of font faces. This means that only those faces needed to render a document will actually be loaded, with the rest being left alone. In fact, a browser that downloads all declared font faces without considering whether they’re actually needed is considered to be buggy.

“@font-face”的目的是允许“延迟加载”字体字体面。这意味着只有那些需要呈现文档的面才会被实际加载,而其余的则被保留下来。实际上,如果一个浏览器下载所有声明的字体而不考虑它们是否真的需要,那么它就会被认为是有 bug 的。

5.2.1 Required Descriptors

All the parameters that define the font you’re referencing are contained within the @font-face { } construct. These are called descriptors, and very much like properties, they take the format descriptor: value;. In fact, most of the descriptor names refer directly to property names, as will be explained in just a moment.

定义所引用字体的所有参数都包含在' @font-face{} '构造中。它们被称为“描述符”,与属性非常相似,它们的格式为“描述符:值”;。实际上,大多数描述符名称直接引用属性名称,稍后将对此进行解释。

There are two required descriptors: font-family and src.

有两个必需的描述符:“font-family”和“src”。

The point of src is pretty straightforward: it lets you define one or more sources for the font face you’re defining, using a comma-separated list if there are in fact multiple sources. You can point to a font face at any URI, but there is a restriction: font faces can only be loaded from the same origin as the stylesheet. Thus, you can’t point your src at someone else’s site and download their font; you’ll need to host a local copy on your own server, or use a font-hosting service that provides both the stylesheet(s) and the font file(s).

“src”的要点非常简单:它允许您为正在定义的字体面定义一个或多个源,如果实际上有多个源,则使用逗号分隔的列表。您可以在任何 URI 上指向字体面,但是有一个限制:字体面只能从与样式表相同的源加载。因此,你不能把你的“src”指向别人的网站,下载他们的字体;您需要在自己的服务器上托管本地副本,或者使用提供样式表和字体文件的字体托管服务。

There is an exception to the same-origin restriction, which is that servers can permit cross-site loading using the HTTP header Access-Control-Allow-Origin.

You may well be wondering how it is that we’re defining font-family here when it was already defined in a previous section. The difference is that this font-family is the font-family descriptor, and the previously-defined font-family was the font-family property. If that seems confusing, stick with me a moment and all should become clear.

您可能很想知道我们在这里是如何定义“font-family”的,而在前面的小节中已经定义了它。区别在于,这个“font-family”是“font-family”描述符,而以前定义的“font-family”是“font-family”“property”。如果这看起来令人困惑,请跟我说一下,一切都会变得清晰起来。

In effect, @font-face lets you create low-level definitions that underpin the fontrelated properties like font-family. When you define a font family name via the descriptor font-family: "SwitzeraADF";, you’re setting up an entry in the user agent’s table of font families for “SwitzeraADF.” It thus joins all the usual suspects like Helvetica, Georgia, Courier, and so forth, as a font you can just refer to in your fontfamily property values:

实际上,@font-face 允许您创建底层定义来支持与字体相关的属性,如“字体家族”。当您通过描述符“font-family: " aadf " ';”定义字体族名称时,您是在用户代理的字体族表中为“aadf”设置一个条目。因此,它加入了所有常见的可疑字体,如 Helvetica、Georgia、Courier 等,成为一种您可以在 fontfamily 属性值中引用的字体:

@font-face {

font-family: "SwitzeraADF"; /* descriptor */

src: url("SwitzeraADF-Regular.otf");

}

h1 {

font-family: SwitzeraADF, Helvetica, sans-serif;

} /* property */Note how the font-family descriptor value and the entry in the font-family property match. If they didn’t match, then the h1 rule would ignore the first font family name listed in the font-family value and move on to the next. As long as the font has cleanly downloaded and is in a format the user agent can handle, then it will be used in the manner you direct, as illustrated in Figure 5-4.

注意“font-family”描述符值和“font-family”属性中的条目如何匹配。如果它们不匹配,那么“h1”规则将忽略“font-family”值中列出的第一个字体姓,并移到下一个。只要下载的字体是干净的,并且是用户代理可以处理的格式,那么它将按照您指定的方式使用,如图 5-4 所示。

图 5-4: Using a downloaded font

In a similar manner, the comma-separated src descriptor value provides fallbacks. That way, if (for whatever reason) the user agent is unable to download the first source, it can fall back to the second source and try to load the file there:

以类似的方式,逗号分隔的“src”描述符值提供了回退。这样,如果(无论什么原因)用户代理不能下载第一个源文件,它可以回到第二个源文件,并尝试加载文件:

@font-face {

font-family: "SwitzeraADF";

src: url("SwitzeraADF-Regular.otf"), url("/fonts/SwitzeraADF-Regular.otf");

}Remember that the same-origin policy generally applies in this case, so pointing to a copy of the font some other server will usually fail, unless said server is set up to permit cross-origin access.

记住,同源策略通常适用于这种情况,所以指向字体的副本时,其他服务器通常会失败,除非所述服务器设置为允许跨源访问。

If you want to be sure the user agent understands what kind of font you’re telling it to use, that can be done with the optional format():

如果你想确保用户代理理解你告诉它使用哪种字体,可以使用可选的“format()”:

@font-face {

font-family: "SwitzeraADF";

src: url("SwitzeraADF-Regular.otf") format("opentype");

}The advantage of supplying a format() description is that user agents can skip downloading files in formats that they don’t support, thus reducing bandwidth use and loading speed. It also lets you explicitly declare a format for a file that might not have a common filename extension and thus be unfamiliar to the user agent:

提供“format()”描述的好处是,用户代理可以跳过下载不支持的格式的文件,从而减少带宽使用和加载速度。它还允许您显式地声明一个文件的格式,可能没有一个通用的文件名扩展名,因此不熟悉的用户代理:

@font-face {

font-family: "SwitzeraADF";

src: url("SwitzeraADF-Regular.otf") format("opentype"), url("SwitzeraADF-Regular.true")

format("truetype");

}The Flash

If you’re a designer or developer of a certain vintage, you may remember the days of FOUC: the Flash of Unstyled Content. This happened in earlier browsers that would load the HTML and display it to the screen before the CSS was finished loading, or at least before the layout of the page via CSS was finished. Thus, what would appear was a split-second of plain ol’ text (using the browser’s default styles) before it was replaced with the CSS-decorated layout.

如果你是某个年份的设计师或开发者,你可能还记得 FOUC 的日子:不加修饰的内容的闪光。这种情况发生在早期的浏览器中,它们会在 CSS 完成加载之前加载 HTML 并将其显示在屏幕上,或者至少在通过 CSS 完成页面布局之前。因此,在它被 css 装饰的布局取代之前,出现的是一秒的普通文字(使用浏览器的默认样式)。

There is a cousin to this problem, which is the Flash of Un-Fonted Text, or FOUFT. This happens when a browser has loaded the page and the CSS and displays the laidout page before it’s done loading custom fonts. This causes text to appear in the default font, or a fallback font, before being replaced by text using the custom-loaded font.

这个问题还有一个类似的问题,即未填充文本的 Flash,或 FOUFT。当浏览器加载了页面和 CSS 并在加载自定义字体之前显示 laidout 页面时,就会发生这种情况。这将导致文本在被使用自定义加载的字体的文本替换之前以默认字体或回退字体出现。

Since the replacement of text with the custom-loaded font face can change its layout size, authors should take care in selecting fallback fonts. If there is a significant height difference between the font used to initially display the text and the custom font eventually loaded and used, significant page reflows are likely to occur. There’s no automated way to enforce this, though font-size-adjust (covered later) can help in supporting user agents. You have to look at your intended font and find other faces that have a similar height.

由于用自定义加载的字体面替换文本可能会更改其布局大小,因此作者在选择回退字体时应该谨慎。如果用于最初显示文本的字体与最终加载和使用的自定义字体之间存在显著的高度差异,则可能会发生显著的页面重新流动。虽然“字体大小-调整”(稍后讨论)可以帮助支持用户代理,但是没有自动执行此操作的方法。你必须查看你想要的字体,并找到其他有相似高度的字体。

The core reason for the “flash” behavior is pretty much the same now as it was then: the browser is ready to show something before it has all the resources on hand, so it goes ahead and does so, replacing it with the prettier version once it can. The FOUC was eventually solved, and it’s likely that some day we’ll look back at the FOUFT the same way we do at the FOUC now. Until then, we’ll have to take comfort in the fact that the FOUFT isn’t usually as jarring as was the FOUC.

“flash”行为的核心原因现在和以前几乎是一样的:浏览器已经准备好在它拥有所有资源之前显示一些东西,所以它继续这样做,一旦可以,就用更漂亮的版本替换它。FOUC 最终被解决了,很可能有一天我们会像现在一样回顾 FOUFT。在那之前,我们不得不接受一个事实,那就是犯规通常不像犯规那样刺耳。

// T5-1

In addition to the combination of url() and format(), you can also supply a font family name (or several names) in case the font is already locally available on the user’s machine, using the aptly-named local():

@font-face {

font-family: "SwitzeraADF";

src: local("Switzera-Regular"), local("SwitzeraADF-Regular "),

url("SwitzeraADF-Regular.otf") format("opentype"), url("SwitzeraADF-Regular.true")

format("truetype");

}In this example, the user agent looks to see if it already has a font family named “Switzera-Regular” or “SwitzeraADF-Regular” available. If so, it will use the name SwitzeraADF to refer to that locally installed font. If not, it will use the url() value to try downloading the remote font.

在本例中,用户代理查看是否已经有名为“- regular”或“aadf - regular”的字体家族可用。如果是这样,它将使用名称“aadf”来指代本地安装的字体。如果没有,它将使用' url() '值尝试下载远程字体。

Note that this capability allows an author to create custom names for locally installed fonts. For example, you could set up a shorter name for Helvetica (or, failing that, Helvetica Neue) like so:

请注意,此功能允许作者为本地安装的字体创建自定义名称。例如,您可以为 Helvetica 设置一个更短的名称(或者,Helvetica Neue),如下所示:

@font-face {

font-family: "H";

src: local("Helvetica"), local("Helvetica Neue");

}

h1,

h2,

h3 {

font-family: H, sans-serif;

}As long as the user has Helvetica installed on their machine, then those rules will cause the first three heading levels to be rendered using Helvetica. It seems a little gimmicky, but it could have a real impact on reducing stylesheet file size in certain situations.

只要用户在他们的机器上安装了 Helvetica,那么这些规则将导致使用 Helvetica 呈现前三个标题级别。这看起来有点花哨,但是在某些情况下,它确实可以减少样式表文件的大小。

On being bulletproof

The tricky part with @font-face is that different browsers of different eras supported different font formats. (To the insider, Table 5-1 reads as a capsule history of downloadable font support.) In order to cover the widest possible landscape, you should turn to what is known as the “Bulletproof @font-face Syntax.” Initially developed by Paul Irish and refined by the folks at FontSpring, it looks like this:

“@font-face”的棘手之处在于,不同时代的不同浏览器支持不同的字体格式。(对于内部人士来说,表 5-1 是可下载字体支持的历史记录。)为了涵盖尽可能广泛的领域,您应该使用所谓的“可靠的‘@font-face’语法”。它最初由保罗·爱尔兰(Paul Irish)开发,并由 FontSpring 的人加以改进,它看起来是这样的:

@font-face {

font-family: "SwitzeraADF";

src: url("SwitzeraADF-Regular.eot");

src: url("SwitzeraADF-Regular.eot?#iefix") format("embedded-opentype"), url("SwitzeraADF-Regular.woff")

format("woff"), url("SwitzeraADF-Regular.ttf") format("truetype"), url("SwitzeraADF-Regular.svg#switzera_adf_regular")

format("svg");

}Let’s break it down piece by piece. The first bit, assigning the font-family name, is straightforward enough. After that, we see:

让我们一块一块地把它拆开。第一部分分配“font-family”名称非常简单。之后,我们看到:

src: url("SwitzeraADF-Regular.eot");

src: url("SwitzeraADF-Regular.eot?#iefix") format("embedded-opentype");This supplies an EOT (Embedded OpenType) to browsers that understand only EOTs —IE6 through IE9. The first line is for IE9 when it’s in “Compatibility Mode,” and the second line hands the same file to IE6-IE8. The ?#iefix bit in that line exploits a parsing bug in those browsers to step around another parsing bug that causes them to 404 any @font-face with multiple formats listed. IE9 fixed its bugs without expanding its font formats, so the first line is what lets it join the party:

这为只理解 EOTs -IE6 到 IE9 的浏览器提供了一个 EOT(嵌入式 OpenType)。第一行是处于“兼容模式”的 IE9,第二行是将相同的文件提交给 IE6-IE8。“?这一行的#iefix 利用了这些浏览器中的一个解析错误,绕过了另一个导致它们 404 所有“@font-face”和列出的多种格式的解析错误。IE9 在没有扩展字体格式的情况下修正了它的缺陷,所以第一行就是它加入的原因:

url("SwitzeraADF-Regular.woff") format("woff"),This line supplies a Web Open Font Format file to browsers that understand it, which includes most modern browsers. At this point, in fact, you’ll have covered the vast majority of your desktop users.

这一行代码为理解它的浏览器(包括大多数现代浏览器)提供了一个 Web 开放字体格式文件。实际上,到目前为止,您已经覆盖了大多数桌面用户。

url("SwitzeraADF-Regular.ttf") format("truetype"),This line hands over the file format understood by most iOS and Android devices, thus covering most of your handheld users:

这一行传递了大多数 iOS 和 Android 设备都能理解的文件格式,从而涵盖了大多数手持用户:

url("SwitzeraADF-Regular.svg#switzera_adf_regular") format("svg");Here, at the end, we supply the only font format understood by old iOS devices. This covers almost all of your remaining handheld users.

在这里,在最后,我们提供了唯一的字体格式理解的老 iOS 设备。这几乎覆盖了您所有的手持用户。

This gets a bit unwieldy if you’re specifying more than a couple of faces, and typing it in even once is kind of a pain in the wrists. Fortunately, there are services available that will accept your font faces and generate all the @font-face rules you need, convert those faces to all the formats required, and hand it all back to you as a single package. One of the best is Font Squirrel’s @Font-Face Kit Generator. Just make sure you’re legally able to convert and use the font faces you’re running through the generator (see the next sidebar, “Custom Font Considerations” on page 161, for more information).

如果您指定了多个面孔,这就变得有些笨拙,甚至一次输入都是一种手腕上的痛苦。幸运的是,有一些服务可以接受您的字体,并生成您需要的所有' @font-face '规则,将这些字体转换为所需的所有格式,然后作为一个单独的包返回给您。其中最好的一个是 Font Squirrel 的@Font-Face 工具包生成器。只要确保你可以合法地转换和使用你运行在生成器中的字体(参见下一个侧边栏,“自定义字体注意事项”,在 161 页,以获得更多信息)。

5.2.2 Other Font Descriptors

In addition to the required font-family and src descriptors, there are a number of optional descriptors that can be used to associate font faces with specific font property values. Just as with font-family, these descriptors (summarized in Table 5-2) correspond directly to CSS properties (explained in detail later in this chapter) and affect how user agents respond to the values supplied for those properties.

Custom Font Considerations

There are two things you need to keep in mind when using customized fonts. The first is that you have the rights to use the font in a web page, and the second is whether it’s a good idea to do so.

在使用定制字体时,需要记住两件事。第一个是您有权在 web 页面中使用字体,第二个是这样做是否是一个好主意。

Much like stock photography, font families come with licenses that govern their use, and not every font license permits its use on the web. You can completely avoid this question by only using FOSS (Free and Open-Source Software) fonts, or by using a commercial service like Fontdeck or Typekit that will deal with the licensing and format conversion issues so you don’t have to. Otherwise, you need to make sure that you have the right to use a font face in the way you want to use it, just the same as you make sure you have the proper license for any images you bought.

就像传统摄影一样,字体家族也有自己的使用许可,但并不是所有的字体许可都能在网上使用。你完全可以通过使用自由/开源软件字体来避免这个问题,或者使用像 Fontdeck 或 Typekit 这样的商业服务来处理授权和格式转换问题,这样你就不必这么做了。否则,你需要确保你有权利以你想要的方式使用字体,就像你确保你有适当的许可证为你购买的任何图像。

In addition, the more font faces you call upon, the more resources the web server has to hand over and the higher the overall page weight will become. Most faces are not overly large—usually 50K to 100K—but they add up quickly if you decide to get fancy with your type, and truly complicated faces can be larger. As you might imagine, the same problems exist for images. As always, you will have to balance appearance against performance, leaning one way or the other depending on the circumstances.

此外,调用的字体越多,web 服务器需要交付的资源就越多,整个页面的权重也就越高。大多数脸型都不是特别大——通常是 5 万到 100 万——但是如果你想让自己的脸型更漂亮,这些脸型加起来会很快,而且真正复杂的脸型可能会更大。可以想象,图像也存在同样的问题。与往常一样,您必须在外观和性能之间取得平衡,根据情况选择一种方式或另一种方式。

Furthermore, just as there are image optimization tools available, there are also font optimization tools. Typically these are subsetting tools, which construct fonts using only the symbols actually needed for display. If you’re using a service like Typekit or Fonts.com, they probably have subsetting tools available, or else do it dynamically when the font is requested.

此外,正如有图像优化工具可用,也有字体优化工具。通常这些是“子集”工具,它们仅使用显示所需的符号来构造字体。如果你使用的是 Typekit 或“Fonts.com”这样的服务,它们可能有可用的子集设置工具,或者在需要字体时动态设置。

// T5-2

Because these font descriptors are optional, they may not be listed in a @font-face rule, but CSS does not allow descriptors to go without default values any more than it does for properties. If an optional descriptor is omitted, then it is set to the default value. Thus, if font-weight is not listed, the default value of normal is assumed.

因为这些字体描述符是可选的,它们可能不会在“@font-face”规则中列出,但是 CSS 不允许描述符没有默认值,就像不允许属性没有默认值一样。如果省略了可选的描述符,则将其设置为默认值。因此,如果没有列出“font-weight”,则假定默认值为“normal”。

Restricting character range

There is one font descriptor, unicode-range, which (unlike the others in Table 5-2) has no corresponding CSS property. This descriptor allows authors to define the range of characters to which a custom font can be applied. This can be useful when using a symbol font, or to ensure that a font face is only applied to characters that are in a specific language.

有一个字体描述符“unicode-range”,它(与表 5-2 中的其他描述符不同)没有相应的 CSS 属性。此描述符允许作者定义可应用自定义字体的字符范围。这在使用符号字体时非常有用,或者可以确保字体只应用于特定语言中的字符。

By default, the value of this property covers the entirety of Unicode, meaning that if a font can supply the glyph for a character, it will. Most of the time, this is exactly what you want. For all the other times, you’ll want to use a specific font face for a specific kind of content. To pick two examples from the CSS Fonts Module Level 3:

默认情况下,这个属性的值覆盖了 Unicode 的全部,这意味着如果一种字体可以为一个字符提供字形,它就可以。大多数时候,这正是你想要的。对于所有其他情况,您将需要为特定类型的内容使用特定的字体。从 CSS 字体模块 3 中挑选两个例子:

unicode-range: U+590-5FF; /* Hebrew characters */

unicode-range: U+4E00-9FFF, U+FF00-FF9F, U+30??; /* Japanese kanji,

hiragana, katakana */In the first case, a single range is specified, spanning Unicode character code point 590 through code point 5FF. This covers the characters used in Hebrew. Thus, an author might specify a Hebrew font and restrict it to only be used for Hebrew characters, even if the face contains glyphs for other code points:

在第一种情况下,指定一个范围,从 Unicode 字符代码点 590 到代码点 5FF。这涵盖了希伯来语中使用的字符。因此,作者可以指定一种希伯来字体,并将其限制为仅用于希伯来字符,即使字体包含其他代码点的符号:

@font-face {

font-family: "CMM-Ahuvah";

src: url("cmm-ahuvah.otf" format("opentype");

unicode-range: U+590-5FF;

}In the second case, a series of ranges are specified in a comma-separated list to cover all the Japanese characters. The interesting feature there is the U+30?? value, which is a special format permitted in unicode-range values. The question marks are wildcards meaning “any possible digit,” making U+30?? equivalent to U+3000-30FF. The question mark is the only “special” character pattern permitted in the value.

在第二种情况下,在逗号分隔的列表中指定了一系列范围,以覆盖所有日语字符。有趣的功能是“U+30??”值,这是“unicode-range”值中允许的一种特殊格式。问号是通配符,意思是“任何可能的数字”,使“U+30??”相当于“U+3000-30FF”。问号是值中唯一允许的“特殊”字符模式。

Ranges must always ascend. Any descending range (e.g., U+400-300) is treated as a parsing error and ignored. Besides ranges, you can also declare a single code point, which looks like U+221E. This is most often useful in conjunction with other code points and ranges, like so:

范围一定要扩大。任何降序范围(例如' U+400-300 ')都被视为解析错误并被忽略。除了范围之外,您还可以声明一个类似于“U+221E”的代码点。这通常与其他代码点和范围一起使用,比如:

unicode-range: U+4E00-9FFF, U+FF00-FF9F, U+30??, U+A5;

/* Japanese kanji, hiragana, and katakana, plus yen/yuan currency symbol*/You could use a single code point to declare that a specific face only be used to render one, and only one, character. Whether or not that’s a good idea is left to you, your design, the size of the font file, and your users’ connection speeds.

您可以使用单个代码点来声明一个特定的 face 只用于呈现一个字符。这是否是个好主意取决于您自己、您的设计、字体文件的大小和用户的连接速度。

Because @font-face is designed to optimize lazy loading, it’s possible to use unicode-range to download only the font faces a page actually needs. Suppose that you have a website that uses a mixture of English, Russian, and basic mathematical operators, but you don’t know which will appear on any given page. There could be all English, a mixture of Russian and math, and so on. Furthermore, suppose you have special font faces for all three types of content. You can make sure a user agent only downloads the faces it actually needs with a properly-constructed series of @font-facerules:

因为“@font-face”是用来优化延迟加载的,所以可以使用“unicode-range”来下载页面实际需要的字体。假设您有一个混合使用英语、俄语和基本数学运算符的网站,但是您不知道哪个操作符会出现在任何给定的页面上。可以是全英语,混合俄语和数学,等等。此外,假设您对所有三种类型的内容都有特殊的字体。你可以确保一个用户代理只下载它实际上需要的脸,用一个适当构造的' @font-face '规则系列:

@font-face {

font-family: "MyFont";

src: url("myfont-general.otf" format("opentype");

}

@font-face {

font-family: "MyFont";

src: url("myfont-cyrillic.otf" format("opentype");

unicode-range: U+04??, U+0500-052F, U+2DE0-2DFF, U+A640-A69F, U+1D2B-1D78;

}

@font-face {

font-family: "MyFont";

src: url("myfont-math.otf" format("opentype");

unicode-range: U+22??; /* equivalent to U+2200-22FF */

}Because the first rule doesn’t specify a Unicode range, it is always downloaded—unless a page happens to contain no characters at all (and maybe even then). The second rule causes myfont-cyrillic.otf to be downloaded only if the page contains characters in its declared Unicode range; the third rule does the same for basic mathematical operators.

因为第一个规则没有指定 Unicode 范围,所以它总是被下载—除非一个页面恰好不包含任何字符(甚至可能不包含任何字符)。第二条规则导致了“myfont-cyrillic”。只可在页面包含其声明的 Unicode 范围内的字符时下载;第三条规则同样适用于基本的数学运算符。

5.2.3 Combining Descriptors

Something that might not be immediately obvious is that you can supply multiple descriptors in order to assign specific faces for specific property combinations. For example, you can assign one face to bold text, another to italic text, and a third to text that is both bold and italic.

有些事情可能不是很明显,您可以提供多个描述符来为特定的属性组合分配特定的面。例如,可以将一个面指定为粗体文本,另一个面指定为斜体文本,第三个面指定为粗体和斜体文本。

This is actually implicit in the fact that any undeclared descriptor is assigned its default value. Let’s consider a basic set of three face assignments:

这实际上是隐式的,因为任何未声明的描述符都会被赋给它的默认值。让我们考虑一组基本的三张脸的分配:

@font-face {

font-family: "SwitzeraADF";

font-weight: normal;

font-style: normal;

font-stretch: normal;

src: url("SwitzeraADF-Regular.otf") format("opentype");

}

@font-face {

font-family: "SwitzeraADF";

font-weight: bold;

font-style: normal;

font-stretch: normal;

src: url("SwitzeraADF-Bold.otf") format("opentype");

}

@font-face {

font-family: "SwitzeraADF";

font-weight: normal;

font-style: italic;

font-stretch: normal;

src: url("SwitzeraADF-Italic.otf") format("opentype");

}Here, we’ve made the implicit explicit: any time a descriptor isn’t being altered, its default value is listed. This is exactly the same as a set of three rules in which we remove every descriptor that shows a value of normal:

这里,我们将隐式设置为显式:只要描述符没有被修改,它的默认值就会被列出。这与我们删除每一个显示‘normal’值的描述符的三组规则完全相同:

@font-face {

font-family: "SwitzeraADF";

src: url("SwitzeraADF-Regular.otf") format("opentype");

}

@font-face {

font-family: "SwitzeraADF";

font-weight: bold;

src: url("SwitzeraADF-Bold.otf") format("opentype");

}

@font-face {

font-family: "SwitzeraADF";

font-style: italic;

src: url("SwitzeraADF-Italic.otf") format("opentype");

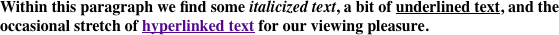

}In all three rules, there is no font-stretching beyond the normal amount, and the values of font-weight and font-style vary by which face is being assigned. So what if we want to assign a specific face to unstretched text that’s both bold and italic?

在这三个规则中,没有超出正常范围的字体拉伸,“字体-权重”和“字体-样式”的值因分配的字体而异。那么,如果我们想将一个特定的面指定给未拉伸的文本,即粗体又斜体呢?

@font-face {

font-family: "SwitzeraADF";

font-weight: bold;

font-style: italic;

font-stretch: normal;

src: url("SwitzeraADF-BoldItalic.otf") format("opentype");

}And then what about bold, italic, condensed text?

然后是粗体,斜体,压缩文本?

@font-face {

font-family: "SwitzeraADF";

font-weight: bold;

font-style: italic;

font-stretch: condensed;

src: url("SwitzeraADF-BoldCondItalic.otf") format("opentype");

}How about normal-weight, italic, condensed text?

那么标准的、斜体的、压缩的文本呢?

@font-face {

font-family: "SwitzeraADF";

font-weight: normal;

font-style: italic;

font-stretch: condensed;

src: url("SwitzeraADF-CondItalic.otf") format("opentype");

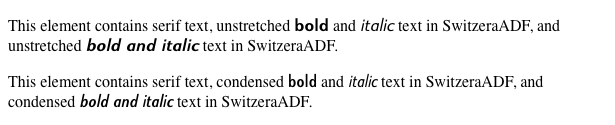

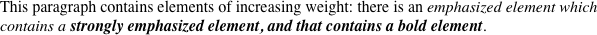

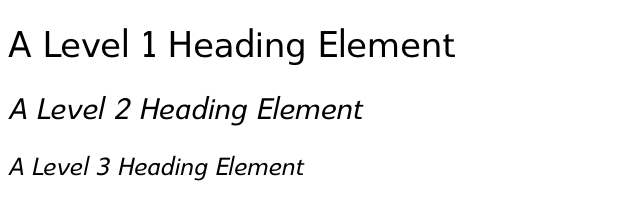

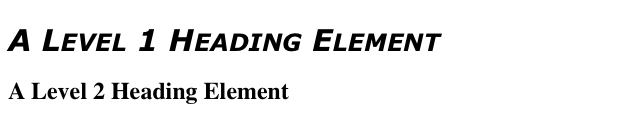

}We could keep this up for quite a while, but let’s stop there. If we take all those rules and strip out anything with a normal value, we end up with this result, illustrated in Figure 5-5:

我们可以继续这样做一段时间,但就到这里吧。如果我们去掉所有这些规则,去掉任何具有“正常”值的东西,就会得到这个结果,如图 5-5 所示:

@font-face {

font-family: "SwitzeraADF";

src: url("SwitzeraADF-Regular.otf") format("opentype");

}

@font-face {

font-family: "SwitzeraADF";

font-weight: bold;

src: url("SwitzeraADF-Bold.otf") format("opentype");

}

@font-face {

font-family: "SwitzeraADF";

font-style: italic;

src: url("SwitzeraADF-Italic.otf") format("opentype");

}

@font-face {

font-family: "SwitzeraADF";

font-weight: bold;

font-style: italic;

src: url("SwitzeraADF-BoldItalic.otf") format("opentype");

}

@font-face {

font-family: "SwitzeraADF";

font-weight: bold;

font-stretch: condensed;

src: url("SwitzeraADF-BoldCond.otf") format("opentype");

}

@font-face {

font-family: "SwitzeraADF";

font-style: italic;

font-stretch: condensed;

src: url("SwitzeraADF-CondItalic.otf") format("opentype");

}

@font-face {

font-family: "SwitzeraADF";

font-weight: bold;

font-style: italic;

font-stretch: condensed;

src: url("SwitzeraADF-BoldCondItalic.otf") format("opentype");

}

图 5-5: Employing a variety of faces

As you can see, there are a lot of possible combinations just for those three descriptors—consider that there are 11 possible values for font-weight, and 10 for font-stretch—but you’ll likely never have to run through them all. In fact, most font families don’t have as many faces as SwitzeraADF offers (24 at last count), so there wouldn’t be much point in writing out all the possibilities. Nevertheless, the options are there, and in some cases you may find that you need to assign, say, a specific face for bold condensed text so that the user agent doesn’t try to compute them for you.

正如您所看到的,仅这三个描述符就有许多可能的组合—考虑到“font-weight”有 11 个可能的值,而“font-stretch”有 10 个可能的值—但是您可能永远不必遍历它们。事实上,大多数字体家族没有 aadf 提供的字体那么多(最新统计为 24 种),所以没有必要把所有的可能性都写出来。然而,选项是存在的,在某些情况下,您可能会发现需要为粗体压缩文本分配一个特定的 face,这样用户代理就不会尝试为您计算它们。

5.3 Font Weights

Now that we’ve covered @font-face and its descriptors, let’s get back to properties. We’re all used to normal and bold text, at the very least, which are sort of the two most basic font weights available. CSS gives you a lot more control over font weights with the property font-weight.

Generally speaking, the heavier a font weight becomes, the darker and “more bold” a font appears. There are a great many ways to label a heavy font face. For example, the font family known as SwitzeraADF has a number of variants, such as SwitzeraADF Bold, SwitzeraADF Extra Bold, SwitzeraADF Light, and SwitzeraADF Regular. All of these use the same basic font shapes, but each has a different weight.

一般来说,字体的粗细越重,字体的颜色就越深,字体的粗细也就越大。有很多方法来标记一个沉重的字体。例如,字体家族 aadf 有很多变体,如 aadf Bold, aadf Extra Bold, aadf Light, aadf Regular。所有这些都使用相同的基本字体形状,但每个都有不同的权重。

So let’s say that you want to use SwitzeraADF for a document, but you’d like to make use of all those different heaviness levels. You could refer to them directly through the font-family property, but you really shouldn’t have to do that. Besides, it’s no fun having to write a stylesheet like this:

假设您想使用 aadf 作为文档,但是您想利用所有这些不同的重级别。您可以通过“font-family”属性直接引用它们,但实际上不必这样做。此外,编写这样的样式表也不好玩:

h1 {

font-family: "SwitzeraADF Extra Bold, sans-serif;}

h2 {font-family: " SwitzeraADF Bold, sans-serif;

}

h3 {

font-family: "SwitzeraADF Bold", sans-serif;

}

h4,

p {

font-family: SwitzeraADF Regular, sans-serif;

}

small {

font-family: "SwitzeraADF Light", sans-serif;

}That’s pretty tedious. It would make far more sense to specify a single font family for the whole document and then assign different weights to various elements. You can do this via @font-face and use the various values for the property font-weight. This is a fairly simple font-weight declaration:

这很乏味。为整个文档指定一个字体族,然后为不同的元素分配不同的权重,这样更有意义。您可以通过' @font-face '实现这一点,并为' font-weight '属性使用不同的值。这是一个相当简单的“字体-权重”声明:

b {

font-weight: bold;

}This declaration says the b element should be displayed using a bold font face; or, to put it another way, a font face that is heavier than the normal font face. This is probably expected behavior, since b does cause text to be bold.

这个声明说“b”元素应该用粗体字体显示;或者,换句话说,一个字体面比普通字体面重。这可能是预期的行为,因为“b”确实会导致文本加粗。

What’s really happening behind the scenes is that a heavier face of the font is used for displaying a b element. Thus, if you have a paragraph displayed using Times, and part of it is bold, then there are really two faces of the same font in use: Times and TimesBold. The regular text is displayed using Times, and the bold text is displayed using TimesBold.

在幕后真正发生的是,字体的粗细面用于显示“b”元素。因此,如果您使用 Times 显示一个段落,并且其中一部分是粗体,那么实际上使用的是相同字体的两个面:Times 和 TimesBold。常规文本使用 Times 显示,粗体文本使用 TimesBold 显示。

5.3.1 How Weights Work

To understand how a user agent determines the heaviness, or weight, of a given font variant (not to mention how weight is inherited), it’s easiest to start by talking about the keywords 100 through 900. These number keywords were defined to map to a relatively common feature of font design in which a font is given nine levels of weight. If a font family has faces for all nine weight levels available, then the numbers are mapped directly to the predefined levels, with 100 as the lightest variant of the font and 900 as the heaviest.

要理解用户代理如何确定给定字体变体的重量(更不用说如何继承重量了),最简单的方法是讨论关键字“100”到“900”。定义这些数字关键字是为了映射到字体设计中一个相对常见的特性,在该特性中,字体具有 9 个级别的权重。如果一个字体系列包含所有 9 个可用的重量级别,那么这些数字将直接映射到预定义的级别,其中“100”是最轻的字体变体,“900”是最重的。

In fact, there is no intrinsic weight in these numbers. The CSS specification says only that each number corresponds to a weight at least as heavy as the number that precedes it. Thus, 100, 200, 300, and 400 might all map to the same relatively lightweight variant; 500 and 600 could correspond to the same heavier font variant; and 700, 800, and 900 could all produce the same very heavy font variant. As long as no keyword corresponds to a variant that is lighter than the variant assigned to the previous keyword, everything will be all right.

事实上,这些数字没有内在的权重。CSS 规范只说明每个数字对应的权重至少与它前面的数字一样重。因此,“100”、“200”、“300”和“400”可能都映射到相同的相对轻量级变体;500 和 600 可以对应相同的较重字体变体;“700”、“800”和“900”都可以产生相同的非常重的字体变体。只要 no 关键字对应的变体比分配给前一个关键字的变体轻,那么一切都会很好。

As it happens, these numbers are defined to be equivalent to certain common variant names, not to mention other values for font-weight. 400 is defined to be equivalent to normal, and 700 corresponds to bold. The other numbers do not match up with any other values for font-weight, but they can correspond to common variant names. If there is a font variant labeled something such as “Normal,” “Regular,” “Roman,” or “Book,” then it is assigned to the number 400 and any variant with the label “Medium” is assigned to 500. However, if a variant labeled “Medium” is the only variant available, it is assigned to 400 instead of 500.

实际上,这些数字被定义为与某些常见的变体名称等价,更不用说“字体权重”的其他值了。“400”被定义为“正常”,“700”对应“粗体”。其他数字与“字体权重”的任何其他值不匹配,但它们可以对应常见的变体名称。如果有一种字体被标记为“Normal”、“Regular”、“Roman”或“Book”,那么它被赋值为“400”,而任何带有“Medium”标签的字体被赋值为“500”。但是,如果标记为“Medium”的变体是惟一可用的变体,则将其指定为“400”而不是“500”。

A user agent has to do even more work if there are fewer than nine weights in a given font family. In this case, it must fill in the gaps in a predetermined way:

如果给定字体族中的权重小于 9,则用户代理必须做更多的工作。在这种情况下,它必须以预定的方式填补空白:

- If the value

500is unassigned, it is given the same font weight as that assigned to400. - If 300 is unassigned, it is given the next variant lighter than

400. If no lighter variant is available,300is assigned the same variant as400. In this case, it will usually be “Normal” or “Medium.” This method is also used for200and100. - If

600is unassigned, it is given the next variant darker than that assigned for500. If no darker variant is available,600is assigned the same variant as500. This method is also used for700,800, and900.

- 如果值“500”未被赋值,它将被赋予与赋值给“400”相同的字体权重。

- 如果 300 没有被赋值,它将被赋予比“400”更轻的下一个变量。如果没有更轻的变体可用,“300”被分配与“400”相同的变体。在这种情况下,它通常是“正常的”或“中等的”。“这个方法也用于‘200’和‘100’。

- 如果' 600 '没有被赋值,它将被赋予比' 500 '赋值更深的下一个变量。如果没有更暗的变体可用,“600”被指定为与“500”相同的变体。此方法也用于' 700 '、' 800 '和' 900 '。

To illustrate this weighting scheme more clearly, let’s look at three examples of font weight assignment. In the first example, assume that the font family Karrank% is an OpenType font, so it has nine weights already defined. In this case, the numbers are assigned to each level, and the keywords normal and bold are assigned to the numbers 400 and 700, respectively. This is the most straightforward example, and therefore the one that almost never occurs in the real world. (It is quite rare for a font family to have nine weight levels, and those that do are usually very expensive.)

为了更清楚地说明这个权重分配方案,我们来看三个字体权重分配的例子。在第一个示例中,假设字体族 Karrank%是 OpenType 字体,因此它已经定义了 9 个权重。在本例中,数字被分配到每个级别,关键字“normal”和“bold”分别分配到数字“400”和“700”。这是最直接的例子,因此在现实世界中几乎从未发生过。(一个字体家族有 9 个重量级别的情况非常罕见,而那些有 9 个重量级别的通常都非常昂贵。)

In our second example, consider the font family SwitzeraADF, which was discussed near the beginning of this section. Hypothetically, its variants might be assigned numeric values for font-weight, as shown in Table 5-3.

在我们的第二个例子中,考虑字体族 aadf,它在本节的开头已经讨论过。假设,它的变体可以为“font-weight”分配数值,如表 5-3 所示。

// T5-3

The first three number values are assigned to the lightest weight. The “Regular” face gets the keyword normal, as expected, and the number weight 400. Since there is a “Medium” font, it’s assigned to the number 500. There is nothing to assign to 600, so it’s mapped to the “Bold” font face, which is also the variant to which 700 and bold are assigned. Finally, 800 and 900 are assigned to the “Black” and “UltraBlack” variants, respectively. Note that this last assignment would happen only if those faces had the top two weight levels already assigned. Otherwise, the user agent might ignore them and assign 800 and 900 to the “Bold” face instead, or it might assign them both to one or the other of the “Black” variants.

前三个数值分配给最轻的权重。“正常”脸的关键字是“正常”,和预期的一样,而“体重”是“400”。因为有一个“中”字体,它被分配给数字“500”。没有任何东西可以赋值给' 600 ',所以它被映射到"粗体"字体面,这也是' 700 '和粗体被赋值的变体。最后,“800”和“900”分别被分配到“黑色”和“超短”变体。注意,最后一次分配只会在那些面已经分配了前两个权重级别的情况下发生。否则,用户代理可能会忽略它们,将“800”和“900”分配给“黑体”,或者将它们都分配给“黑色”变体中的一个或另一个。

For our third and final example, let’s consider a stripped-down version of Times. In Table 5-4, there are only two weight variants: “TimesRegular” and “TimesBold.”

对于我们的第三个也是最后一个例子,让我们考虑一个简化版的 Times。在表 5-4 中,只有两个权重变量:“TimesRegular”和“TimesBold”。

// T5-4

The assignment of the keywords normal and bold is to the regular-weight and boldweight faces, as you might expect. As for the numbers, 100 through 300 are assigned to the “Regular” face because there isn’t a lighter face available. 400 is assigned to “Regular” as expected, but what about 500? It is assigned to the “Regular” (or normal) face because there isn’t a “Medium” face available; thus, it is assigned the same font face as 400. As for the rest, 700 goes with bold as always, while 800 and 900, lacking a heavier face, are assigned to the next-lighter face, which is the “Bold” font face. Finally, 600 is assigned to the next-heavier face, which is the “Bold” face.

关键字“normal”和“bold”的赋值是针对常规权重和粗体权重的面,正如您所期望的那样。至于数字,“100”到“300”被分配给“普通”脸,因为没有浅色脸可供选择。“400”被指定为“常规”,但是“500”呢?它被指定为“正常”(或“正常”)脸,因为没有“中等”脸可用;因此,它被分配了与“400”相同的字体面。至于其他字体,“700”和“粗体”总是搭配在一起,而“800”和“900”没有更重的字体,被分配给下一个更轻的字体,即“粗体”字体。最后,“600”被分配给下一个更重的脸,即“粗体”脸。

font-weight is inherited, so if you set a paragraph to be bold:

font-weight是继承的,所以如果你设置一个段落为'粗体':

p.one {

font-weight: bold;

}Then all of its children will inherit that boldness, as we see in Figure 5-6.

图 5-6: Inherited font-weight

This isn’t unusual, but the situation gets interesting when you use the last two values we have to discuss: bolder and lighter. In general terms, these keywords have the effect you’d anticipate: they make text more or less bold compared to its parent’s font weight. First, let’s consider bolder.

5.3.2 Getting Bolder

If you set an element to have a weight of bolder, then the user agent first must determine what font-weight value was inherited from the parent element. It then selects the lowest number which corresponds to a font weight darker than what was inherited. If none is available, then the user agent sets the element’s font weight to the next numerical value, unless the value is already 900, in which case the weight remains at 900. Thus, you might encounter the following situations, illustrated in Figure 5-7:

p {

font-weight: normal;

}

p em {

font-weight: bolder;

} /* results in bold text, evaluates to '700' */

h1 {

font-weight: bold;

}

h1 b {

font-weight: bolder;

} /* if no bolder face exists, evaluates to '800' */

div {

font-weight: 100;

} /* assume 'Light' face exists; see explanation */

div strong {

font-weight: bolder;

} /* results in normal text, weight '400' */

图 5-7: Text trying to be bolder

In the first example, the user agent moves up the weight ladder from normal to bold; in numeric terms, it jumps from 400 to 700. In the second example, h1 text is already set to bold. If there is no bolder face available, then the user agent sets the weight of b text within an h1 to 800, since that is the next step up from 700 (the numeric equivalent of bold). Since 800 is assigned to the same font face as 700, there is no visible difference between normal h1 text and bold h1 text, but the weights are different nonetheless.

In the last example, paragraphs are set to be the lightest possible font weight, which we assume exists as a “Light” variant. Furthermore, the other faces in this font family are “Regular” and “Bold.” Any em text within a paragraph will evaluate to normal since that is the next-heaviest face within the font family. However, what if the only faces in the font are “Regular” and “Bold”? In that case, the declarations would evaluate like this:

/* assume only two faces for this example: 'Regular' and 'Bold' */

p {

font-weight: 100;

} /* looks the same as 'normal' text */

p span {

font-weight: bolder;

} /* maps to '700' */As you can see, the weight 100 is assigned to the normal font face, but the value of font-weight is still 100. Thus, any span text that is descended from a p element will inherit the value of 100 and then evaluate to the next-heaviest face, which is the “Bold” face with a numerical weight of 700.

Let’s take this one step further and add two more rules, plus some markup, to illustrate how all of this works (see Figure 5-8 for the results):

/* assume only two faces for this example: 'Regular' and 'Bold' */

p {

font-weight: 100;

} /* looks the same as 'normal' text */

p span {

font-weight: 400;

} /* so does this */

strong {

font-weight: bolder;

} /* even bolder than its parent */

strong b {

font-weight: bolder;

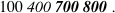

} /*bolder still */<p>

This paragraph contains elements of increasing weight: there is a

<span

>span element that contains a

<strong>strongly emphasized element and a <b>bold element</b></strong></span

>.

</p>

图 5-8: Moving up the weight scale

In the last two nested elements, the computed value of font-weight is increased because of the liberal use of the keyword bolder. If you were to replace the text in the paragraph with numbers representing the font-weight of each element, you would get the results shown here:

在最后两个嵌套元素中,由于关键字“bold”的自由使用,“font-weight”的计算值增加了。如果你用代表每个元素的“字体-权重”的数字代替段落中的文本,你会得到如下结果:

<p>

100

<span>

400 <strong> 700 <b> 800 </b> </strong> </span

>.

</p>The first two weight increases are large because they represent jumps from 100 to 400 and from 400 to bold (700). From 700, there is no heavier face, so the user agent moves the value of font-weight one notch up the numeric scale (800). Furthermore, if you were to insert a strong element into the b element, it would come out like this:

前两次增重幅度很大,因为它们代表从“100”跳到“400”,从“400”跳到“700”。从' 700 '开始,没有较重的面,因此用户代理将' font-weight '的值向上移动一个级别(' 800 ')。此外,如果你将一个“强”元素插入到“b”元素中,结果会是这样的:

<p>

100

<span>

400

<strong>

700 <b> 800 <strong> 900 </strong> </b>

</strong> </span

>.

</p>If there were yet another b element inserted into the innermost strong element, its weight would also be 900, since font-weight can never be higher than 900. Assuming that there are only two font faces available, then the text would appear to be either regular or bold, as you can see in Figure 5-9:

如果在最里面的“强”元素中插入另一个“b”元素,那么它的重量也应该是“900”,因为字元的重量不可能高于“900”。假设只有两种字体可用,那么文本将显示为规则或粗体,如图 5-9 所示:

<p>

regular

<span>

regular

<strong>

bold <b> bold <strong> bold </strong> </b>

</strong> </span

>.

</p>

图 5-9: Visual weight, with descriptors

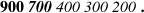

5.3.3 Lightening Weights

As you might expect, lighter works in just the same way, except it causes the user agent to move down the weight scale instead of up. With a quick modification of the previous example, you can see this very clearly:

/* assume only two faces for this example: 'Regular' and 'Bold' */

p {

font-weight: 900;

} /* as bold as possible, which will look 'bold' */

p span {

font-weight: 700;

} /* this will also be bold */

strong {

font-weight: lighter;

} /* lighter than its parent */

b {

font-weight: lighter;

} /* lighter still */<p>

900

<span>

700

<strong>

400 <b> 300 <strong> 200 </strong> </b>

</strong> </span

>.

</p>

<!-- ...or, to put it another way... -->

<p>

bold

<span>

bold

<strong>

regular <b> regular <strong> regular </strong></b>

</strong></span

>.

</p>Ignoring the fact that this would be entirely counterintuitive, what you see in Figure 5-10 is that the main paragraph text has a weight of 900. When the strong text is set to be lighter, it evaluates to the next-lighter face, which is the regular face, or 400 (the same as normal) on the numeric scale. The next step down is to 300, which is the same as normal since no lighter faces exist. From there, the user agent can reduce the weight only one numeric step at a time until it reaches 100 (which it doesn’t do in the example). The second paragraph shows which text will be bold and which will be regular.

图 5-10: Making text lighter

5.3.4 The font-weight descriptor

With the font-weight descriptor, authors can assign faces of varying weights to the weighting levels permitted by the font-weight property. For example, the following rules explicitly assign five faces to six different font-weight values:

@font-face {

font-family: "SwitzeraADF";

font-weight: normal;

src: url("f/SwitzeraADF-Regular.otf") format("opentype");

}

@font-face {

font-family: "SwitzeraADF";

font-weight: bold;

src: url("f/SwitzeraADF-Bold.otf") format("opentype");

}

@font-face {

font-family: "SwitzeraADF";

font-weight: 300;

src: url("f/SwitzeraADF-Light.otf") format("opentype");

}

@font-face {

font-family: "SwitzeraADF";

font-weight: 500;

src: url("f/SwitzeraADF-DemiBold.otf") format("opentype");

}

@font-face {

font-family: "SwitzeraADF";

font-weight: 700;

src: url("f/SwitzeraADF-Bold.otf") format("opentype");

}

@font-face {

font-family: "SwitzeraADF";

font-weight: 900;

src: url("f/SwitzeraADF-ExtraBold.otf") format("opentype");

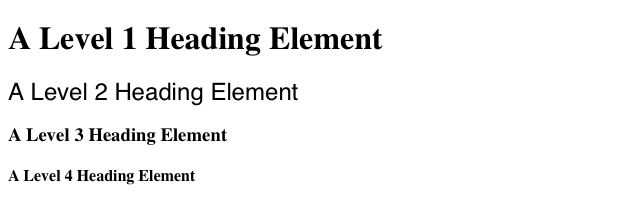

}With these faces assigned, the author now has a number of weighting levels available for his use, as illustrated in Figure 5-11:

h1, h2, h3, h4 {font: 225% SwitzeraADF, Helvetica, sans-serif;}

h1 {font-weight: 900;}

h2 {font-size: 180%; font-weight: 700;}

h3 {font-size: 150%; font-weight: 500;}

h4 {font-size: 125%; font-weight: 300;}

.

图 5-11: Using declared font-weight faces

In any given situation, the user agent picks which face to use depending on the exact value of a font-weight property, using the resolution algorithm detailed in the earlier section, “How Weights Work” on page 167. Authors may use any value for the font-weight descriptor that is permitted for the font-weight property except the inherit keyword.

5.4 Font Size

The methods for determining font size are both very familiar and very different.

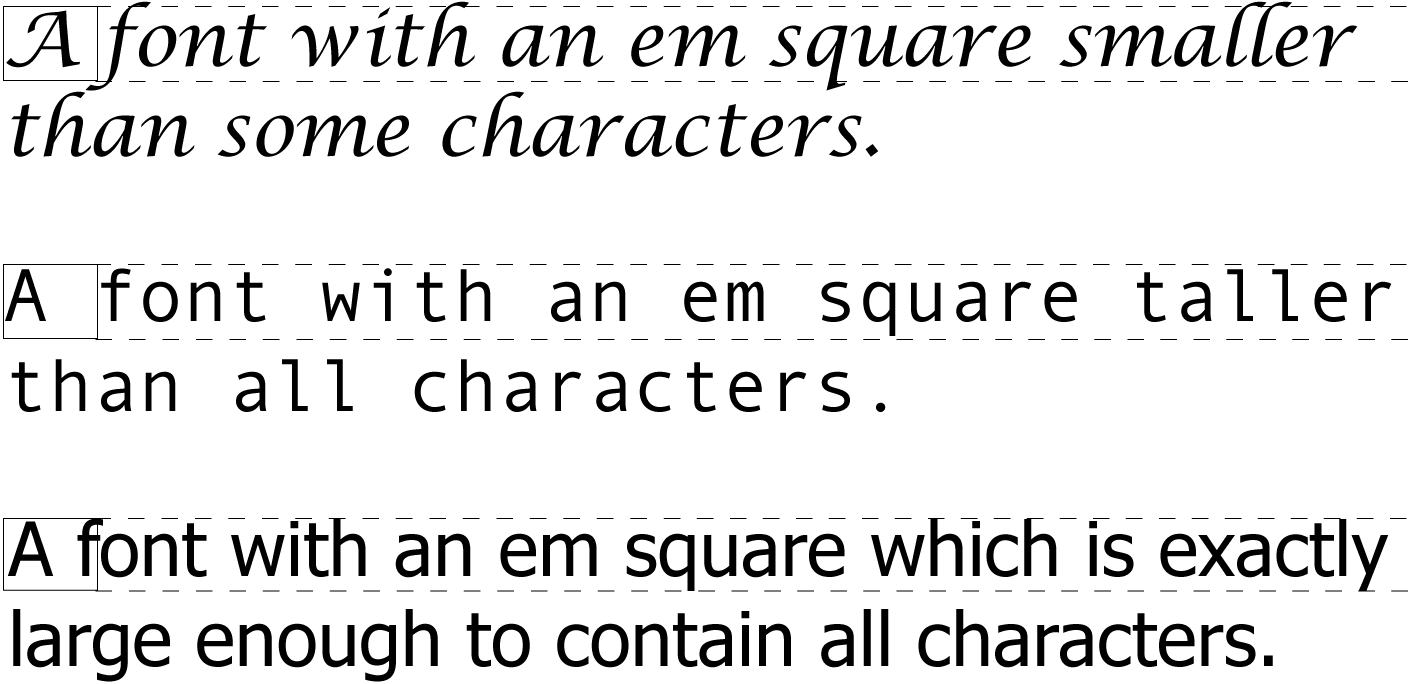

In a fashion very similar to the font-weight keywords bolder and lighter, the property font-size has relative-size keywords called larger and smaller. Much like what we saw with relative font weights, these keywords cause the computed value of font-size to move up and down a scale of size values, which you’ll need to understand before you can explore larger and smaller. First, though, we need to examine how fonts are sized in the first place.

In fact, the actual relation of the font-size property to what you see rendered is determined by the font’s designer. This relationship is set as an em square (some call it an em box) within the font itself. This em square (and thus the font size) doesn’t have to refer to any boundaries established by the characters in a font. Instead, it refers to the distance between baselines when the font is set without any extra leading (line-height in CSS). It is quite possible for fonts to have characters that are taller than the default distance between baselines. For that matter, a font might be defined such that all of its characters are smaller than its em square, as many fonts do. Some hypotheti‐

cal examples are shown in Figure 5-12.

图 5-12: Font characters and em squares

Thus, the effect of font-size is to provide a size for the em box of a given font. This does not guarantee that any of the actual displayed characters will be this size.

5.4.1 Absolute Sizes

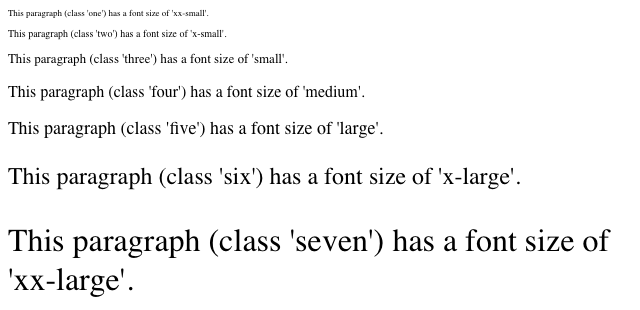

Having established all of that, we turn now to the absolute-size keywords. There are seven absolute-size values for font-size: xx-small, x-small, small, medium, large, x-large, and xx-large. These are not defined precisely, but are relative to each other, as Figure 5-13 demonstrates:

p.one {

font-size: xx-small;

}

p.two {

font-size: x-small;

}

p.three {

font-size: small;

}

p.four {

font-size: medium;

}

p.five {

font-size: large;

}

p.six {

font-size: x-large;

}

p.seven {

font-size: xx-large;

}According to the CSS1 specification, the difference (or scaling factor) between one absolute size and the next is about 1.5 going up the ladder, or 0.66 going down. Thus, if medium is the same as 10px, then large should be the same as 15px. This was later determined to be too large a scaling factor. In CSS2 it was suggested that it be somewhere between 1.0 and 1.2, and in CSS3 drafts a complicated series is provided (for example, small is listed as eight-ninths the size of medium, while xx-small is threefifths). In all case, the scaling factors are guidelines, as user agents are free to alter them for any reason.

图 5-13: Absolute font sizes

Working from the assumption that medium equals 16px, for different scaling factors, we get the absolute size equivalents shown in Table 5-5. (The values shown are rounded-off integers.)

// T5-5

5.4.2 Relative Sizes

Comparatively speaking, the keywords larger and smaller are simple: they cause the size of an element to be shifted up or down the absolute-size scale, relative to their parent element, using the same scaling factor employed to calculate absolute sizes. In other words, if the browser used a scaling factor of 1.2 for absolute sizes, then it should use the same factor when applying relative-size keywords:

p {

font-size: medium;

}

strong,

em {

font-size: larger;

}<p>

This paragraph element contains

<strong

>a strong-emphasis element which itself contains

<em

>an emphasis element that also contains

<strong>a strong element.</strong></em

></strong

>

</p>

<p>

medium

<strong

>large <em> x-large <strong>xx-large</strong> </em>

</strong>

</p>Unlike the relative values for weight, the relative-size values are not necessarily constrained to the limits of the absolute-size range. Thus, a font’s size can be pushed beyond the sizes for xx-small and xx-large. For example:

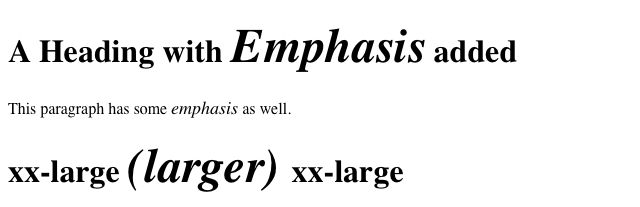

h1 {

font-size: xx-large;

}

em {

font-size: larger;

}<h1>A Heading with <em>Emphasis</em> added</h1>

<p>This paragraph has some <em>emphasis</em> as well.</p>As you can see in Figure 5-14, the emphasized text in the h1 element is slightly larger than xx-large. The amount of scaling is left up to the user agent, with the scaling factor of 1.2 being preferred but not required. The em text in the paragraph is shifted one slot up the absolute-size scale (large).

图 5-14: Relative font sizing at the edges of the absolute sizes

User agents are not required to increase or decrease font size beyond the limits of the absolute-size keywords.

5.4.3 Percentages and Sizes

In a way, percentage values are very similar to the relative-size keywords. A percentage value is always computed in terms of whatever size is inherited from an element’s parent. Percentages, unlike the size keywords previously discussed, permit much finer control over the computed font size. Consider the following example, illustrated in Figure 5-15:

body {

font-size: 15px;

}

p {

font-size: 12px;

}

em {

font-size: 120%;

}

strong {

font-size: 135%;

}

small,

.fnote {

font-size: 70%;

}<body>

<p>

This paragraph contains both <em>emphasis</em> and

<strong>strong emphasis</strong>, both of which are larger than their parent

element. The <small>small text</small>, on the other hand, is smaller by a

quarter.

</p>

<p class="fnote">This is a 'footnote' and is smaller than regular text.</p>

<p>

12px <em> 14.4px </em> 12px <strong> 16.2px </strong> 12px

<small> 9px </small> 12px

</p>

<p class="fnote">10.5px</p>

</body>

图 5-15: Throwing percentages into the mix

In this example, the exact pixel size values are shown. These are the values calculated by the browser, regardless of the actual displayed size of the characters onscreen.

Incidentally, CSS defines the length value em to be equivalent to percentage values, in the sense that 1em is the same as 100% when sizing fonts. Thus, the following would yield identical results, assuming that both paragraphs have the same parent element:

p.one {

font-size: 166%;

}

p.two {

font-size: 1.6em;

}When using em measurements, the same principles apply as with percentages, such as the inheritance of computed sizes and so forth.

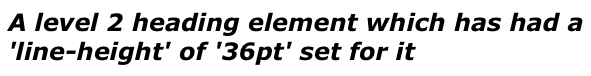

5.4.4 Font Size and Inheritance

Figure 5-12 also demonstrates that, although font-size is inherited in CSS, it is the computed values that are inherited, not percentages. Thus, the value inherited by the strong element is 12px, and this value is modified by the declared value 135% to arrive at 16.2px. For the “footnote” paragraph, the percentage is calculated in relation to the font-size value that’s inherited from the body element, which is 15px. Multiplying that value by 75% yields 11.25px.

As with the relative-size keywords, percentages are effectively cumulative. Thus, the following markup is displayed as shown in Figure 5-16:

p {

font-size: 12px;

}

em {

font-size: 120%;

}

strong {

font-size: 135%;

}<p>

This paragraph contains both<em

>emphasis and <strong>strong emphasis</strong></em

>, both of which are larger than the paragraph text.

</p>

<p>

12px <em>14.4px <strong> 19.44px </strong></em> 12px

</p>

图 5-16: The issues of inheritance

The size value for the strong element shown in Figure 5-16 is computed as follows:

12 px × 120% = 14.4 px

14.4 px × 135% = 19.44 px (possibly rounded to 19 px for display; see the next section)

The problem of runaway scaling can go the other direction, too. Consider for a moment a document that is nothing but a series of unordered lists, many of them nested inside other lists. Some of these lists are four nested levels deep. Imagine the effect of the following rule on such a document:

ul {

font-size: 80%;

}Assuming a four-level deep nesting, the most deeply nested unordered list would have a computed font-size value 40.96 percent the size of the parent of the top-level list. Every nested list would have a font size 80 percent as big as its parent list, causing each level to become harder and harder to read.

Rounding for display

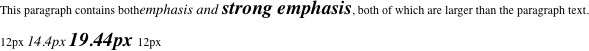

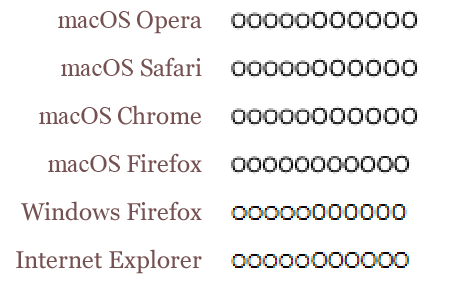

In most modern browsers, while fractional font-size values are maintained internally, they are not always used by rendering engines. For example, study the letterforms in Figure 5-17.

In all cases, the O characters increase by 0.1 pixels in size as you go from left to right. Thus, the leftmost O has a font-size of 10px, the one at the midpoint has a size of 10.5px, and the one on the right is 11px.

As Figure 5-17 reveals, different browser/OS combinations yield different results. For example, Opera, Safari, and Chrome for macOS show an abrupt jump from 10 pixels to 11 pixels at the 10.5px position. Internet Explorer and Firefox for Windows (both 7 and 8) do the same. Firefox for macOS, on the other hand, looks like it has a smooth line of same-size text. In fact, the characters are all being drawn subtly differently, thanks to their subtly different font-size values. It’s hard to see without squinting (or a ruler), but the fact that it’s hard to tell there is an increase in size from one end of the line to the other is evidence enough.

图 5-17: Fractional font sizes

Nevertheless, every browser will yield up the same subpixel font-size values if you use an inspector or query the value directly via DOM scripting. The third O from the right will show a computed value of 10.8px, regardless of the size of the character displayed onscreen.

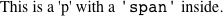

Keywords and monospace text

There’s an interesting wrinkle to font size keywords and inheritance that becomes apparent when you look at what some browsers do with monospace text (e.g., Courier). Consider the following, illustrated in Figure 5-18:

p {

font-size: medium;

} /* the default value */

span {

font-family: monospace;

font-size: 1em;

}<p>This is a 'p' with a <span>'span'</span> inside.</p>

图 5-18: Monospace size oddities

The default value of medium is generally resolved to 16px, assuming the user hasn’t changed the browser preferences (where the default text sizes are set). Indeed, if you query the paragraph text outside the span, inspectors will tell you that the computed font-size of the text is 16px (again, assuming the user hasn’t changed the preferences).

So you might expect the monospaced span to also have 16-pixel text. That’s exactly the case in some browsers; but in others, it will be 13px.

The reason for this is that while the computed font-size of the paragraph is 16px, the keyword medium is what’s passed down through inheritance. Thus, the span starts out with font-size: medium. As a result, it looks to the user’s preference settings to determine the proper size, and most browsers are set to a 13px default size for all monospace text. This causes them to display 13-pixel monospace text in a 16-pixel parent, even though the monospace text was explicitly set to font-size: 1em.

The effect carries through even with font sizes other than 1em (or 100%); in the following case, the monospace text will have a computed size of 26px instead of 32px (once more assuming the browser defaults have not changed):

p {

font-size: medium;

} /* the default value */

span {

font-family: monospace;

font-size: 2em;

}<p>This is a 'p' with a <span>'span'</span> inside.</p>Note that not all browsers actually do this: some override the medium sizing assumptions in favor of scaling off the computed font-size of the parent. This leads to inconsistent text display across browsers.

As it happens, there is a way to work around this problem that works for all known browsers, at least as of late 2017. It goes like this:

p {

font-size: medium;

} /* the default value */

span {

font-family: monospace, serif;

font-size: 1em;

}<p>This is a 'p' with a <span>'span'</span> inside.</p>See the extra serif in the font-family there? That somehow triggers a switch that makes all browsers treat font-size: 1em as being 100 percent of the paragraph’s computed font-size, not a medium-derived value. This is cross-browser-consistent and illustrated in Figure 5-19.

图 5-19: Monospace size harmony

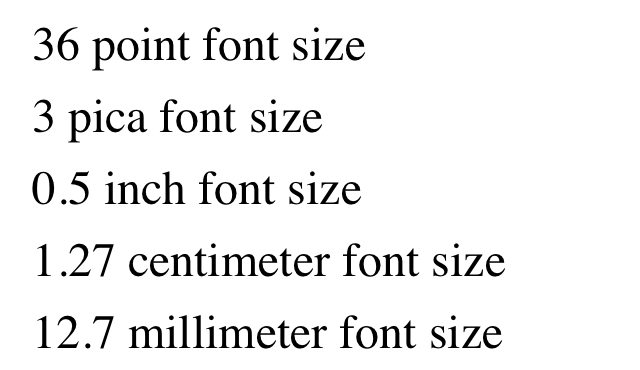

5.4.5 Using Length Units

The font-size can be set using any length value. All of the following font-size declarations should be equivalent:

p.one {

font-size: 36pt;

}

p.two {

font-size: 3pc;

}

p.three {

font-size: 0.5in;

}

p.four {

font-size: 1.27cm;

}

p.five {

font-size: 12.7mm;

}The display in Figure 5-20 assumes that the user agent knows how many dots per inch are used in the display medium. Different user agents make different assumptions—some based on the operating system, some based on preferences settings, and some based on the assumptions of the programmer who wrote the user agent. Nevertheless, the five lines should always have the same font size. Thus, while the result may not exactly match reality (for example, the actual size of p.three may not be half an inch), the measurements should all be consistent with one another.

图 5-20: Various font sizes

There is one more value that is potentially the same as those shown in Figure 5-20, and that’s 36px, which would be the same physical distance if the display medium is 72 pixels per inch (ppi). However, there are very few monitors with that setting anymore. Most desktop displays are much higher, in the range of 96 ppi to 120 ppi; and mobile devices go much higher, currently in the 300 ppi to 500 ppi range.

Despite these variations between operating systems and devices, many authors choose to use pixel values for font sizes. This approach seems especially attractive when mixing text and raster images (GIF, JPG, PNG, etc.) on a web page, since text can (in theory) be set to the same height as graphic elements on the page by declaring font-size: 11px; or something similar, as illustrated by Figure 5-21.

图 5-21: Keeping text and graphics in scale with pixel sizes

Using pixel measurements for font-size is certainly one way to get “consistent” results with font-size (and, indeed, with any length at all), but there is a drawback. Not every browser makes it easy (or even possible) to resize text set in pixels, and there are situations where pixel-sized text can be badly sized in mobile devices that pretend to be full-screen devices (such as most versions of the iPhone). For these reasons alone, pixel-sizing text is generally not recommended.

5.4.6 Automatically Adjusting Size

Two of the main factors that influence a font’s legibility are its size and its x-height. The number that results from dividing the x-height by the font-size is referred to as the aspect value. Fonts with higher aspect values tend to be legible as the font’s size is reduced; conversely, fonts with low aspect values become illegible more quickly. CSS provides a way to deal with shifts in aspect values between font families with the property font-size-adjust.

The goal of this property is to preserve legibility when the font used is not the author’s first choice. Because of the differences in font appearance, while one font may be legible at a certain size, another font at the same size is difficult or impossible to read.

A good example is to compare the common fonts Verdana and Times. Consider Figure 5-22 and the following markup, which shows both fonts at a font-size of 10px:

p {

font-size: 10px;

}

p.cl1 {

font-family: Verdana, sans-serif;

}

p.cl2 {

font-family: Times, serif;

}

图 5-22: Comparing Verdana and Times

The text in Times is much harder to read than the Verdana text. This is partly due to the limitations of pixel-based display, but it is also because Times becomes harder to read at smaller font sizes.

As it turns out, the ratio of x-height to character size in Verdana is 0.58, whereas in Times it is 0.46. What you can do in this case is declare the aspect value of Verdana, and the user agent will adjust the size of the text that’s actually used. This is accomplished using the formula:

Declared font-size ×

(font-size-adjust value ÷ aspect

value of available font) = Adjusted font-sizeSo, in a situation where Times is used instead of Verdana, the adjustment is as follows:

10px × (0.58 ÷ 0.46) = 12.6px

which leads to the result shown in Figure 5-23:

p {

font: 10px Verdana, sans-serif;

font-size-adjust: 0.58;

}

p.cl2 {

font-family: Times, serif;

}

图 5-23: Adjusting Times

The catch is that to allow a user agent to intelligently make size adjustments, it first has to know the aspect value of the fonts you specify. User agents that support @font-face will be able to pull that information directly from the font file, assuming the files contain the information—any professionally-produced font should, but there’s no guarantee. If a font file doesn’t contain the aspect value, a user agent may try to compute it; but again, there’s no guarantee that they will or even can.

Assuming that the user agent can find or figure out aspect values, the auto value for font-size-adjust is a way of getting the desired effect even if you don’t know the actual aspect value of your first-choice font. For example, given that the user agent can determine that the aspect value of Verdana is 0.58, then the following will have the same result as that shown in Figure 5-23:

p {

font: 10px Verdana, sans-serif;

font-size-adjust: auto;

}

p.cl2 {

font-family: Times, serif;

}Declaring font-size-adjust: none; will suppress any adjustment of font sizes. This is the default state.